‘At Twilight’ - Simon Starling Commentary | The Common Guild

MUSICIAN O God protect me

From a horrible deathless body

In Shinto tradition, twilight is a moment of portal. The mundane world and the spirit world open onto each other and it’s possible to make contact with the supernatural, inducing a restorative animation across the gap. A similar condition of mediation and intermediacy is generated by Simon Starling’s exhibition ‘At Twilight’ through the resurrection of canonical, modernist writers by canonical, modernist artists.

‘At Twilight’ responds to WB Yeats’s ‘At The Hawk’s Well’ (1916), a one-act play loosely based on the legends of Cúchulainn, an Irish mythological hero. ‘At the Hawk’s Well’ incorporates elements of Noh, a form of Japanese theatre originating in the 14th century, which Yeats and Ezra Pound were fascinated by in the early 20th Century. The two poets collaborated on the play, which fused Western High Modernism, Celtic folklore, and Japanese traditional theatre, during the three years they lived together in Ashdown Forest. Starling’s project ‘At Twilight’ restores elements of Yeats’s play while reconnecting the Japanese and Western themes and symbols it contains.

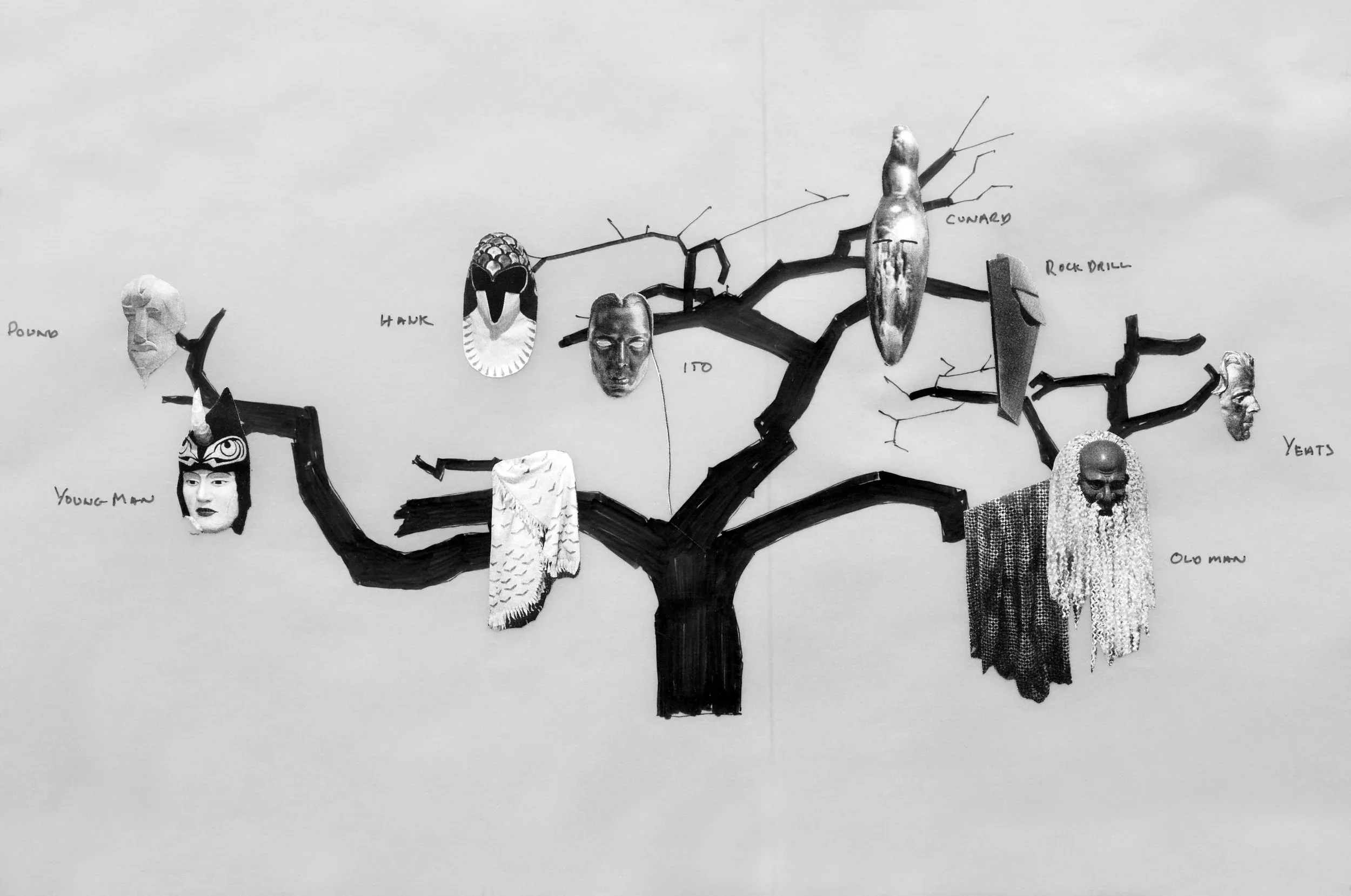

Held across three floors of the building, the exhibition’s scale is reflective of the density of allusions and references that occupy the work. The expansive and hybrid wealth of influence in the exhibition is represented in a ‘mind map’, at the centre of which is a drawing of a blasted tree, with masks of the various characters perched on its branches. The map acts as a microcosmic communication of the capacity of the exhibition as an enactment of cultural hybridity and collaboration.

The majority of the exhibition comprises masks – made by the Japanese master mask-maker Yasuo Miichi – of the characters in Yeats’s and Starling’s play, perched on blasted rhododendron trees. The masks face the mirrors in the gallery’s exhibition spaces, turning the mirrors into portal-like objects, and allowing the masks to exist between time and space. While the masks are of characters, they are diverse in their design[1], their meaning and their utility, reflecting the nature of Yeats’s fixation with them throughout his life and work[2], and demonstrating their value to Starling’s practice as multivalent signs. The masks themselves are modelled after and depict various artists from Yeats and Pound’s milieu: the masks of the Old Man, Young Man, and Guardian of the Well are styled after Edmund Dulac’s costume designs; Nancy Cunard - writer, socialite, activist and muse for many modernist writers including Pound - is represented in a mask styled after Constantin Brancusi’s sculptural portrait of her; and Pound’s own mask is styled after his sculpture portrait by the artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.

A model of the stage on which Starling’s performance took place is included in the exhibition and exists as a site for projection literally and more obliquely. A film of the Hawk’s Dance, choreographed by Javier de Frutos, is projected onto a maquette of the stage for the play on the gallery’s lower floor. In a costume replicating Edmund Dulac’s original design, Thomas Edwards dances against the music of Joshua Abrams and Natural Information Society, emphasising the connective potential of this engagement with cross-cultural and cross-temporal modes.

The dance performs “the romantic notion of what may have happened”[3] in the original production and animates the inanimate, conjuring and finding what has been lost in terms of the temporal, the factual, and the generative. The fragmentary nature of the documentation of the first performance has allowed Starling creative space for conjecture around the performance and development of the ideas therein. For Starling, the limitations of documentation are treated as being “more potent”[4], more productive, more projective than the absolute nature of a fully documented production.

This productivity is elemental to Yeats’s work ‘Anima Hominis’[5], in which he describes the relationship between the self and the anti-self as being necessary for art. The text discusses the nature of artistic creation as a “quarrelling with the self”, which necessitates a doubling of the psyche to antagonise the artist’s preconceptions and develop an active critical relationship with the self and the art they are mutually producing. The artist must therefore assume the mask of the second self. In Starling’s play, this relationship with the self is represented through the two actors portraying fictionalised versions of both the artist himself and theatre director and collaborator Graham Eatough who perform versions of Yeats and Pound, and so on, through the ability afforded to the actors by their masks.

While the exhibition presented Eeyore’s front and back as separated, the reconnection of Eeyore’s body and therefore the reconnection of the two people inside the costume in the play can be seen as the reconnected self and anti-self that are unified through this quarrelling and artistic investigation. Eeyore’s lost tail/tale becomes symbolic of how these creative limitations are worked over, and of the connective potential of speculative engagement with multitudinous cultural artefacts.

The wall text that accompanies the Pound mask, styled after Gaudier-Brzeska’s stone portrait, mentions what linguist Noboku Tsukui calls the “endemic misunderstandings and omissions” in Pound’s translation of Noh plays, which nevertheless demonstrated “excellent insight and appreciation” of their nature. The slippages of time in ‘At Twilight', the moments lost or in the process of being lost, communicate the capacity of the exhibition as a study of disjunctive hybrid contexts and of their productive qualities.

“The fact is this is more difficult

than I thought,

I ought -

(Very good indeed)

I ought

to begin again,

But it is easier

To stop.”[6]

[1] Styled after Edmund Dulac, Jacob Epstein, Isamu Noguchi, Constantin Brancusi, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.

[2] See Yeats’s essay ‘Anima Hominis’ from Per Amica Silentia Lunae (1918); and the poems: ‘The Mask,’ A Vision’, ‘Ego Dominus Tuus,’ and ‘Supernatural Songs’, among others, concern the idea of the mask or of wearing an ‘image’ of the self.

[3] Javier de Frutos. The Common Guild, ibid.

[4] Simon Starling. At Twilight: A play for two actors, three musicians, one dancer, eight masks (and a donkey costume)’. The Common Guild. 2016. [https://vimeo.com/189020688].

[5] WB Yeats. ‘Anima Hominis’, 1917. Published in Per Amica Silentia Lunae, 1918. Los Angeles: Hardpress Publishing, 2013.

[6] A.A. Milne. Eeyore’s ‘POEM’, from Pooh’s Letters from the Hundred Acre Wood. From Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928). London: Methuen Children’s Books, 1998.